Should web apps use PAKEs?

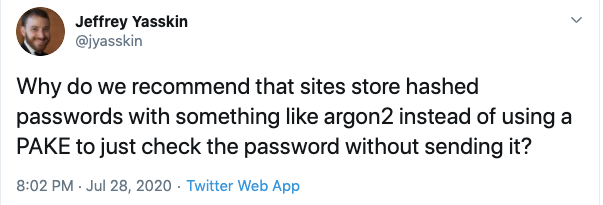

My colleague Jeffrey Yasskin asked an interesting question on Twitter:

Jeffrey is referring to Password Authenticated Key Exchange (PAKE) protocols. PAKEs allow two parties to negotiate a cryptographic key based on a password, which might be known by one or both of the parties. When people talk about using PAKEs in the web setting, however, they usually aren’t directly interested in negotiating a cryptographic key. Instead, they’re interested in using a PAKE to authenticate a user, and they’re specifically interested in PAKEs because some PAKEs allow a client to prove to a server that the client knows the correct password without revealing the password to the server. In contrast, when using traditional password-based authentication, the client sends the password to the server, and the server compares it with a value stored in its database (hopefully hashed with a strong password hashing function).

Not sending the password to a server is appealing for two reasons:

- The server can’t leak the password if it never sees the password. In traditional password-based authentication, we partially mitigate this risk by hashing the password when it’s stored in a database, so that a database breach won’t leak the password. Some developers worry about leaking passwords before they reach the database – for example, passwords might get accidentally written to frontend log files that get leaked – and using a PAKE could mitigate this risk.

- A malicious server can’t steal the password if it never sees the password. However, this goal is irrelevant to Jeffrey’s question about web apps implementing PAKEs. The web server provides the JavaScript code that implements the PAKE, so a malicious server could just steal the password directly on the client. (However, it is interesting to think about how the browser itself might intervene to stop malicious servers from obtaining the password; see Browser-mediated PAKEs below.)

If web apps were to use PAKEs, the security gain would be via the first property: the server can’t leak the password. My position is that PAKEs provide a very marginal security gain in the web app setting (funnily enough, many years ago I was to blame for exorcising one of the few PAKE implementations on the web), but to argue that position coherently, I first need to discuss why web developers care about leaking passwords in the first place.

Why do we hash passwords, anyway?

I’m not talking about how we hash passwords – e.g., which password hashing function to use, how many rounds, etc. I’m talking about a much more basic question: why do we bother hashing passwords rather than just sticking them in the database like other data? (Sidenote: I think this would make a great warm-up interview question for a security engineer… of course now that I’m blogging about, I won’t be able to use it.)

At first glance, it might seem obvious that websites hash passwords so that a database breach doesn’t yield long-term access to all the site’s users’ accounts. But, if an attacker gains read access to a website’s database, the attacker can likely leak session cookies or other bearer tokens as well as all the other sensitive user data that the website handles. The main reason we hash passwords is to mitigate users’ tendency to reuse passwords across different services (in other words, to protect against credential stuffing attacks in which a leaked password at one service is reused at another). If a website’s database gets breached, it is a catastrophic security incident for that website regardless of whether the attacker leaks plaintext passwords or other data. But if the attacker leaks plaintext passwords, the breach is also a catastrophic security incident for other websites. The value of hashing passwords is to prevent a security incident at one service from spreading laterally across huge swaths of the web.

Back to PAKEs

That’s why my answer to Jeffrey’s question was that, in the web setting, PAKEs don’t buy you much that client-side password hashing doesn’t also buy you (and client-side password hashing is much simpler). Both protect against credential stuffing attacks in the event of any server data leak, which, as I argued above, is the main threat that password protections aim to mitigate. A PAKE is stronger in that it prevents a server data leak from yielding long-term access to users’ accounts. In contrast, leaked client-side-hashed passwords do give the attacker access to users’ accounts on that service, because the hashed password effectively is the password. But I just don’t find that very compelling in light of all the other interesting data (session cookies, sensitive user data, etc.) that an attacker would be able to access with a server data leak.

This is not to say that I recommend client-side password hashing – just that any web developer considering implementing a PAKE should take a close look at their threat model and consider if client-side hashing is a much simpler way to get what they want. Personally I’d recommend that web developers focus their cycles on moving users towards stronger auth in the form of WebAuthn, rather than investing in either a PAKE or client-side password hashing.

A historical sidenote

Reasonable people can disagree on the answer to Jeffrey’s question, and another reasonable answer might be “historical accident.” PAKEs were patent-encumbered for some period of time, and some had less than ideal security properties. Furthermore, until the WebCrypto API came along and offered native implementations of cryptographic algorithms to JavaScript, implementing a PAKE would have involved hand-rolling cryptographic primitives in a slow language that isn’t particularly well-suited to it. So it could be that the advice to use a strong password hashing function took root in the web developer community and wasn’t easy to overturn once stronger PAKEs and native crypto implementations came along.

Browser-mediated PAKEs

PAKEs don’t provide protection against malicious servers in the web setting, because a malicious server could serve evil JavaScript that reads the plaintext password off the page as the user is typing it. This problem invites an alternative design to implementing a PAKE in JavaScript. What if the PAKE was implemented in the browser itself and exposed via JavaScript API, with trustworthy browser UI collecting the password from the user so that malicious JavaScript can’t steal it?

At first glance, a browser-mediated PAKE appears to be a powerful anti-phishing tool as well as a protection against server data leaks. But there are some problems with this idea:

- It poses a usable security and ecosystem challenge. The vast majority of websites would have to migrate to the browser-mediated PAKE in order for users to get out of the habit of typing passwords directly into webpages. Otherwise, users wouldn’t notice anything amiss as they type their password directly into a phishing webpage, even if the victim website used the browser-mediated PAKE. Even if all websites magically migrated away from plaintext passwords to a browser-mediated PAKE, a phishing website could likely convincingly spoof the browser password entry UI to trick the user into typing the password into the page, where it is accessible to JavaScript.

- Historically, browser-mediated authentication hasn’t seen widespread adoption on the consumer web. Browser developers tend to view HTTP Basic Auth as legacy cruft that we’re stuck with due to entrenchment in enterprises. The Credential Management API was a more recent attempt, and not many websites use it. I’m not sure why this is1, but one hypothesis is that web developers don’t like to have the browser mediate user authentication and prefer to integrate it into the look and feel of their website. WebID is a brand-new attempt aimed at moving federated login into the browser to prevent cross-site tracking, so it will be interesting to see if and how that gains adoption.

- If we could solve these usable security challenges, particularly the challenge of training users to not type passwords directly into webpages, then browsers could defend against phishing with much simpler means, e.g. by getting users to log in to websites exclusively using a password manager that refuses to fill credentials on the wrong sites. The marginal value of adopting PAKEs then reduces to the same question I discussed above: is the complexity of a PAKE worth the benefits in the event of a server data leak when you consider all the other sensitive data that could be leaked?

One final approach I’ll mention: TLS includes PAKE ciphersuites. One could imagine browsers using this feature as a way of implementing a browser-mediated PAKE. I think this is unlikely to achieve widespread adoption in browsers and web servers, or solve any of the security problems I’ve discussed. It suffers from all the usability and adoption challenges I just mentioned, plus it’s implemented at the wrong layer for web applications: TLS-terminating frontends don’t typically know about application authentication state. Similarly, TLS client certificates aren’t widely used outside of enterprises (though client certs suffer from other problems that further inhibit their adoption). I think TLS PAKE ciphersuites are probably designed for non-browser use cases.

Overall, one can construct various theories as to why web apps don’t implement PAKEs, but my personal theory is that the marginal security gain is just not worth the effort and complexity, and I predict that we won’t see widespread PAKE adoption on the web.

Many thanks to Zakir Durumeric, Chris Palmer, and Mike West for their feedback on this post.

-

Esteemed Credential Management spec editor Mike West has another theory: he thinks that Credential Management doesn’t provide enough value on top of plain old autofill, and that something like a PAKE might be compelling enough to gain wider adoption. (On the other hand, using a PAKE-based Credential Management API would impose significantly more server-side implementation work than using today’s Credential Management API, and that might influence the adoption dynamics.) ↩